Why the search for the graviton is the most impossible—and important—quest in physics?

Imagine you are at a party. It’s the Standard Model party. Everyone who is anyone is there. The Electron is mingling near the snacks; the Photon is literally lighting up the room; the Higgs Boson is moving through the crowd, giving everyone mass.

But there is a ghost in the room. You can feel its presence—it’s the reason your feet are stuck to the floor and why the punch doesn’t float out of the bowl. But when you turn to look for the host, the one responsible for this order, there is no one there.

This is the Graviton. It is the hypothetical elementary particle that mediates the force of gravity, and it is the central character in the greatest unsolved mystery of modern physics.

The Profile of a Ghost

If we can’t see it, how do we know what it looks like? Remarkably, theoretical physics gives us a very precise “wanted” poster for the graviton, derived purely from the laws of relativity and quantum mechanics.

If the graviton exists, it has two non-negotiable properties:

- It must be massless. Gravity has an infinite range. You can feel the Sun’s gravity from 93 million miles away; galaxies feel each other across the void of the cosmos. In quantum field theory, forces with infinite range must be carried by massless particles (just like the photon).

- It must be a Spin-2 Boson. This is the smoking gun.

To understand why “Spin-2” is so important, we have to look at the source of the force.

- Electromagnetism comes from the “four-current” (electric charge and current), which is a first-order tensor. Therefore, its carrier particle, the Photon, has Spin-1.

- Gravity comes from the stress–energy tensor (T_{\mu\nu}). This is a complex beast that describes energy density, momentum density, and stress (pressure and shear). Because its source is a second-order tensor, the particle carrying the message must be Spin-2.

The Magnet and the Paperclip

If we know what we are looking for, why haven’t we found it? The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) found the Higgs Boson, so why not this?

The answer lies in the Feebleness Problem.

Gravity is, effectively, the weakling of the fundamental forces. We don’t realize this because we usually experience gravity created by massive objects (like Earth). But strip away the planet, and the force vanishes into a whisper.

Consider the “Magnet and Paperclip” analogy:

Place a paperclip on your desk. The entire Earth—all 6 \times 10^{24} kilograms of it—is pulling that paperclip down. Now, take a tiny fridge magnet and hold it over the paperclip. Snap. The paperclip jumps up to the magnet.

That tiny magnet just defeated the gravitational pull of the entire planet. That is how weak gravity is compared to electromagnetism—roughly $10^{36} times weaker.

The Impossible Detector

Because gravity is so weak, individual gravitons interact with matter so rarely that catching one is statistically impossible.

To detect a particle, you usually need it to hit your detector and transfer energy. Neutrinos are famous for passing through light-years of lead without stopping, but gravitons make neutrinos look like brick walls.

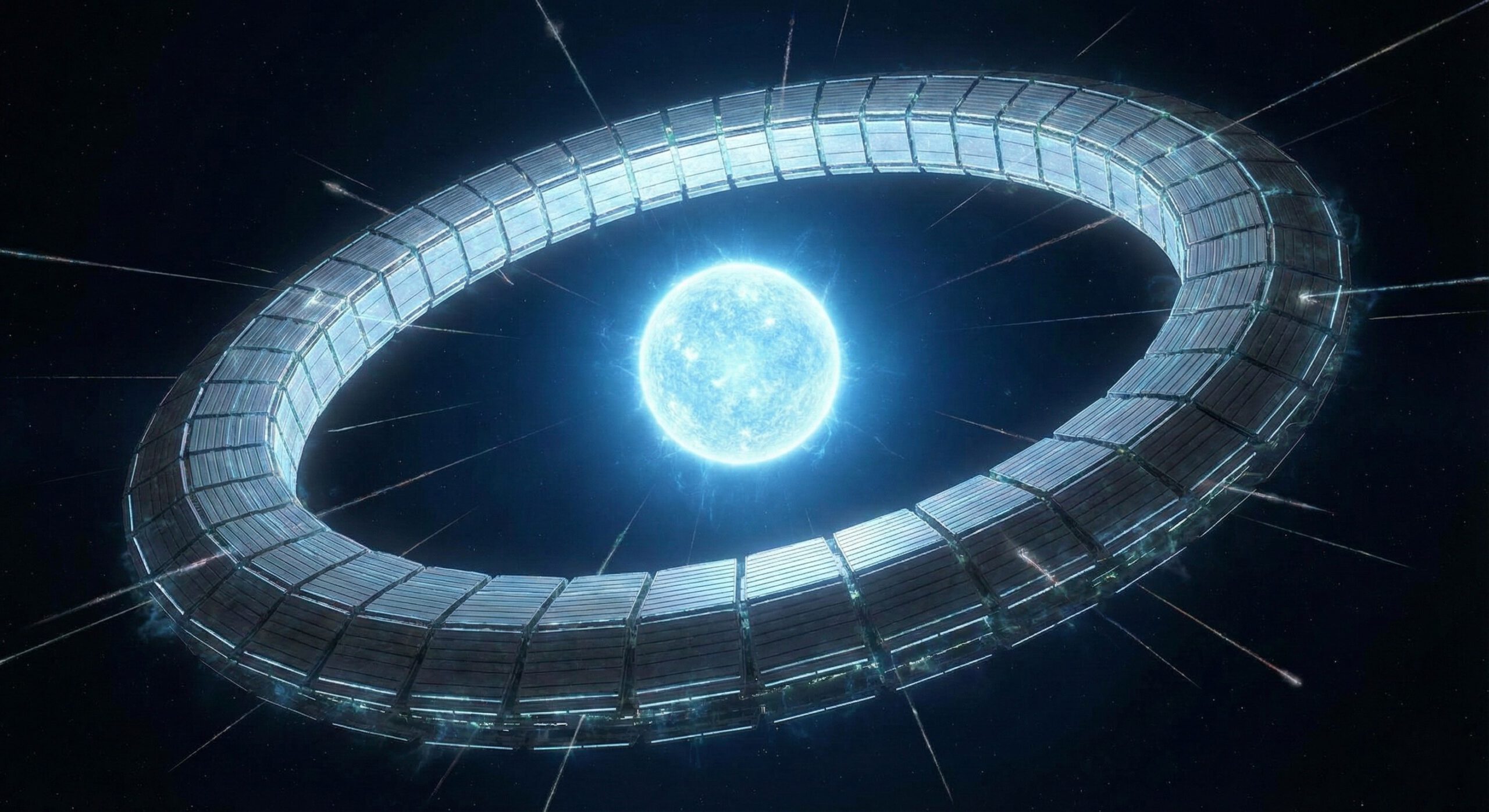

Physicists Tony Rothman and Stephen Boughn crunched the numbers on what it would take to detect a single graviton. The results were disheartening.

To have a fighting chance of detecting just one graviton every 10 years, you would need a detector built with the mass of Jupiter. But you can’t just park it anywhere; you would need to place this Jupiter-sized detector in a tight orbit around a neutron star (a source of intense gravity).

Even if you managed this engineering miracle, the background noise from the universe (neutrinos, cosmic rays) would likely drown out the signal anyway.

Why We Keep Searching

If it’s impossible to find, why does it matter?

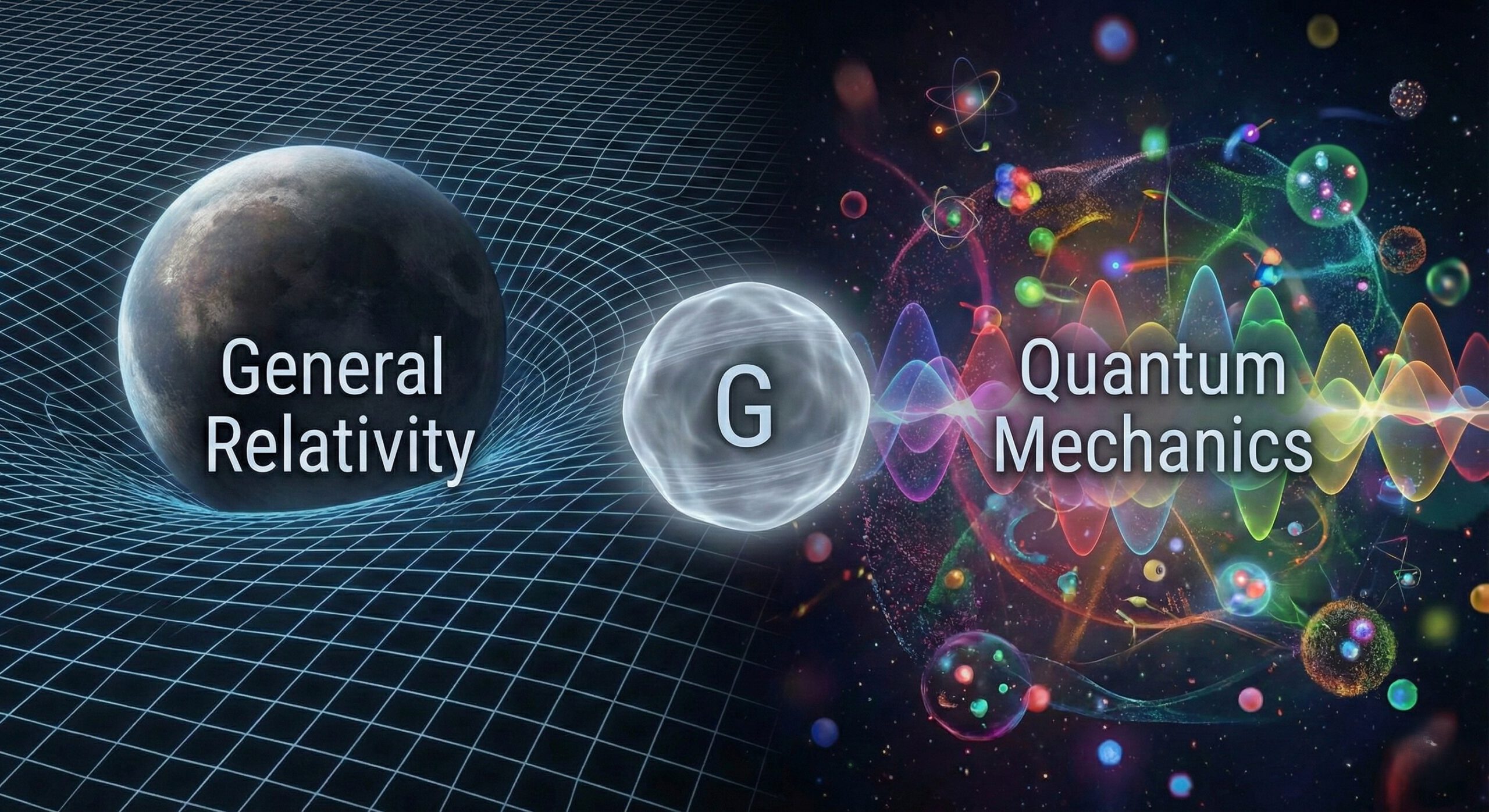

Because the graviton is the missing bridge. On one side of the river, we have General Relativity (Einstein’s world of curved space and time). On the other, we have Quantum Mechanics (the jittery, pixelated world of particles).

The graviton is the only thing that belongs to both worlds. It is a quantum particle that creates the curvature of spacetime. Finding it—or proving it doesn’t exist—is the only way to end the war between physics’ two greatest theories and finally understand the true nature of reality.

For now, the graviton remains the ghost at the party: felt by everyone, seen by no one.